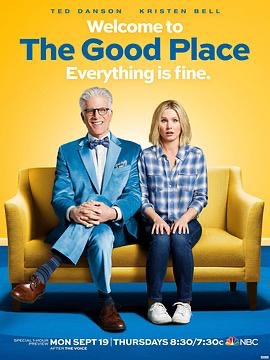

The Good Place Season 1

Kristen Bell, actress from *House of Lies*, and Ted Danson, actor from *CSI: Cyber*, will star in the 13-episode comedy series *The Good Place*, which was directly ordered by NBC and created by Mike Schur. Bell's role in this series does not mean she will leave Showtime's comedy shows; rather, her excellent performance in *House of Lies* opened the opportunity for her to star in *The Good Place*, so she can manage both projects. Danson had expressed last summer that he was very interested in trying a half-hour comedy, and when *The Good Place* found him, he chose this script out of many others. The show follows Eleanor (played by Bell), a woman from New Jersey who suddenly realizes she is not a good person. As a result, she decides to begin a new chapter in her life to learn what being "good" and "bad" truly means and to make up for her past mistakes. Danson plays Michael, who, through a series of coincidences, becomes Eleanor's mentor on her journey of self-improvement.

User Reviews

{{ review.title }}

You can learn philosophy by watching a sitcom?

I never thought that a sitcom could seamlessly incorporate philosophical theories while making us laugh. A fictional afterlife "Good Place" certainly serves as a perfect setting to practice philosophical ideas.

- Categorical Imperative

When Chidi discovers that Eleanor does not belong to the Good Place and contemplates whether to lie to help her, he asks himself: Should he help Eleanor according to the moral principles of the Categorical Imperative? This question perfectly triggers Chidi's decision-making paralysis and causes him stomach pain...

Immanuel Kant introduced the concept of "Categorical Imperative," which requires a person to act consistently according to immutable moral principles, no matter how external circumstances change. According to Kant’s theory, lying, stealing, or any other immoral act has no excuse. Even a white lie, done with good intentions, is still immoral.

Since Eleanor does not belong to the Good Place, if Chidi helps her, it would involve deception and cheating, which would be considered immoral according to Kant. However, on the other hand, Eleanor asks Chidi to help her become a better person. Refusing to help someone improve is another form of immorality. Chidi feels that whatever choice he makes is immoral, leading to a moral dilemma that gives him stomach pain.

Another example of the "Categorical Imperative" is when Chidi gives insincere praise to his friend’s hideously ugly shoes. Even if it is out of kindness, it’s still lying, which violates the Categorical Imperative. Thus, Chidi cannot sleep over this small white lie and feels compelled to tell his friend the truth once the surgery is done.

So, what kind of answer would satisfy Kant? A misleading answer would be acceptable, such as: "I have never seen shoes like this (beautiful/ugly)!" In Kant’s view, a misleading answer is not immoral because, when lying is an option, a misleading statement is itself a form of respect for moral commands.

2. Utilitarianism

Compared to Kant’s Categorical Imperative, Utilitarianism is undoubtedly a philosophy that is easier for most people (including Eleanor) to understand: one should choose the actions that achieve the "greatest good" for the greatest number, even if it means sacrificing the interests of a few. Utilitarianism sounds flawless until faced with dilemmas like the "trolley problem."

It is said that later seasons of The Good Place perfectly reproduce the trolley problem, but in the first season, there is already a Utilitarian dilemma: Chidi struggles with whether to help Eleanor because, on one hand, helping her become a better person and stay in the Good Place would maximize overall happiness. However, if Eleanor stays, it means Chidi’s true soulmate will never appear, which sacrifices his personal happiness. Once again, Chidi is at a loss, guided by philosophical theories.

3. The Moral Value of Motivation

In the second half of the first season, the four-person team hopes to raise Eleanor’s score to keep her in the Good Place, so Eleanor performs many "good deeds," such as holding doors for others, organizing apology parties, and giving gifts. However, none of these actions affect her score.

This brings us back to Kant (who probably contributed over half of The Good Place ’s philosophical theories). Kant believes that "the moral value of an action lies in its motivation." If the motivation is to satisfy personal interests, then the action cannot be considered moral. Therefore, all of Eleanor’s good deeds, done with the selfish motive of staying in the Good Place, are not counted in the scoring system. A similar situation happens with Tehani: Even though she raised 600 billion dollars through her charity event, her impure motives mean she still does not belong to the "Good Place." So, when Eleanor’s motivation changes and she performs good deeds not for selfish reasons, those actions finally become "moral deeds" and are counted in the score.

The big twist in the last episode of The Good Place is certainly interesting, but isn't it just as fascinating to see real-life acting of philosophical theories and moral dilemmas in a sitcom? It certainly brings a smile and makes you reflect.

Reflections Triggered by the Realm of Ultimate Goodness

Recently, during my lunch break, I finished watching The Good Place. It’s a light-hearted comedy, and the general premise is that the protagonist, Eleanor, dies and discovers she is in "the Good Place." However, she realizes that she wasn’t a good person while alive, so she decides to do everything she can to become a good person in the afterlife. The story revolves around her and three other characters, with the plot unfolding based on their lives before death, their secrets, and their journey after death.

What attracted me to this show is that it's light and easy to watch, and it presents philosophical thoughts in a very simple and humorous way, which kept me hooked (I'm a curious beginner when it comes to philosophy). Another reason I found the show unique is that I heard it hired two philosophy advisors to help with the writing.

Now, I’ll share a few philosophical thoughts that came to mind after finishing the show:

- The Trolley Problem - Utilitarianism vs. Deontological Ethics: One of the highlights of this show is that it brings the famous "trolley problem" into the story. The Trolley Problem is a thought experiment introduced by Scottish philosopher Philippa Foot. Here's the gist:

Imagine a trolley speeding down a track, and not far ahead, there’s a fork in the track. On the main track, there are five people tied up. If the trolley keeps going straight, it will kill all five of them. On the side track, there’s one person. If you decide to intervene by pulling a lever, the trolley will switch to the side track, killing the one person. Should you sacrifice one person to save five?

This thought experiment has many variations. For example, what if the person on the side track is your close friend? How would you decide then?and more Through the portrayal of this scene, I gained some understanding of the different debates surrounding this issue, and it led me to further explore the distinction between utilitarianism and deontological ethics. The question is: when we do something, should we consider the outcome and its consequences, or should we consider the intention behind the action itself?

For a utilitarian, the outcome of an action is extremely important. They would choose to pull the lever because they want to save five people’s lives, even though it means sacrificing one person’s life to achieve that result.

On the other hand, for a deontologist, everyone has equal rights. The rights of the person on the one track and the five people on the other are the same. The decision-maker, by intervening, is essentially deciding to kill one person. Since the fate of the original five people does not directly concern us, a deontologist might choose not to intervene in order to avoid killing someone.

The Good Place portrays this classic trolley problem and its variations, which is very interesting.

- If it’s been 500 years since anyone entered Heaven, and the outcome is final, why should we still do good? Another concept in The Good Place is the "scoring system." In the original setup, after someone dies, the cosmic scoring system reviews their entire life, and based on the score, they are sent either to the Good Place or the Bad Place.

For example, picking a flower from the side of the road might deduct five points, while volunteering at a nursing home could add ten points. The importance of good deeds and bad deeds determines the score.

In the show, the Good Place’s architect’s office has a portrait of a mortal who is the only person who ever guessed the scoring system correctly after eating a magical mushroom.

However, in Heaven, it’s been 500 years since anyone has entered the Good Place. Why?

For example, after the person who figured out the scoring system from the magical mushrooms began eating plants that had minimal impact on the environment, and only consumed produce from orchards, it didn’t necessarily earn them a positive score. This is because they might have eaten crops irrigated with toxic pesticides, or they might have used a smartphone made in a sweatshop to order all-vegan takeout. The delivery driver used a car that emitted excessive greenhouse gases. And the CEO of the takeout company had a history of sexual harassment. How do you evaluate the morality of such actions?

This plot illustrates the complexity of every action in our increasingly modern society. We can no longer evaluate the morality of a person’s actions based on a single standard.

- Free Will vs. Determinism (to be continued)

I will continue to record my thoughts after finishing the show.

Let me know if you'd like me to continue or adjust anything!

After her death, she finally began to learn how to be a good person.

When we were kids, we often pointed at the characters on TV and asked our parents, "Is he a bad guy or a good guy?" This was our earliest way of understanding others. As we grew older and entered society, we realized that human nature is complex, so we stopped categorizing people simply as good or bad. We also became more indifferent and selfish, wondering, why should it matter whether someone is good or bad? Besides, we occasionally cut in line, tell lies, or do small "evil" acts that go against our conscience, but this doesn't necessarily mean we're bad people. After all, no one is watching us, recording every moment of our actions, adding points for every good deed and deducting points for every bad one. When we die, no one will assign a score to our lives to determine what kind of afterlife we get: if we fail to pass, we might be tortured endlessly, living a life worse than death; if we score high enough, we might live the perfect life we dreamed of but never achieved in life.

Now, imagine you learn the secret of the afterlife and start doing good deeds in hopes of getting a high score. Can you then achieve your desired outcome? With this question in mind, let's explore the high-concept comedy The Good Place .

The protagonist, Eleanor, wakes up in a strange place and is greeted by a white-haired man named Michael, who is the architect and manager of The Good Place , welcoming her to the afterlife. In this world, the afterlife isn't divided into Heaven and Hell but rather into The Good Place and The Bad Place. The Good Place is divided into numerous communities, each tailored to the individual. It features personal assistants who can fulfill every wish with a snap of a finger. Isn’t this the life everyone dreams of? Michael congratulates Eleanor, telling her that after an evaluation, she was deemed a high-scoring good person based on her life as a human rights lawyer, so she was sent to The Good Place. The standards for good and bad are just as I described earlier. Eleanor, however, finds it odd that all these great historical figures like Mozart, Picasso, and Elvis Presley are in The Bad Place, while she herself, who might not deserve to be in The Good Place, is there. She comments on how strange the judging standards are, though she doesn’t think much of it at the time. This sets up a twist in the first season.

Next comes another important setup: each person in The Good Place has a soulmate, carefully matched by the system. The show slowly unveils more intriguing details about the world of The Good Place throughout the season, so don’t worry about spoilers. Each episode is only 20 minutes, and there are 13 episodes, so there's plenty of action.

Eleanor’s soulmate is Chidi, an ethics professor who has dedicated his life to academic research and is still writing the first draft of his book, which is 3,600 pages long. After a brief exchange of greetings, Eleanor reveals a shocking secret: there's been a huge mistake. She is indeed Eleanor, but not the good Eleanor. She is, in fact, a scammer who sold fake nutritional products to elderly people without feeling guilty. She belongs in The Bad Place, but the system mistakenly mixed her up with another good person named Eleanor.

This truth pushes Chidi into his first moral dilemma: Should he lie to help Eleanor stay in The Good Place, or should he tell the truth, which would send her to The Bad Place to face eternal punishment? This dilemma not only tortures Chidi but also becomes a growing concern for Eleanor as the story progresses.

For anyone, The Good Place is a perfect world. You can get anything you want. How could Eleanor bear to leave? To avoid being discovered and sent to The Bad Place, Eleanor decides to learn how to be a good person. However, for someone like her — selfish, unkind, and always looking for ways to exploit others — this is an incredibly difficult journey. She has to study deep philosophical theories with her soulmate Chidi while also battling her own nature, pretending to do good deeds. But her tendency to think of herself first creates chaos and trouble, putting herself and Chidi in dangerous situations, and shaking the very foundation of The Good Place. They face one moral dilemma after another. As the plot unfolds, more secrets about The Good Place are revealed, and it turns out Eleanor isn’t the only flaw in the system.

Eleanor's problems grow more complex as she realizes the consequences of the "small evils" she committed in life. The bad things she does now in The Good Place could harm the entire community. What will she do? Will the bad Eleanor be able to stay in The Good Place, or can she truly become a good person in the end? I won’t spoil the ending, as the twists in the plot may surprise you, both in terms of the storyline and our understanding of human nature.

The Good Place is not only full of mind-blowing plot twists but also cleverly integrates serious philosophical questions into the story through a light-hearted comedy format. Although the show explores the afterlife, it also offers deep reflections on how we should live our lives.

Further Reading:

- Yale University Open Course on Philosophy and Death

- Plato's Phaedo

- Hume's A Treatise of Human Nature

- Russell's Philosophy and Happiness

- Laozi's Tao Te Ching

- Aristotle's Metaphysics

The Good Place 1

Chidi, who causes suffering to those around him due to his rigidity and indecision, and Tahani, who, under the guise of doing good deeds, is actually motivated by a desire for attention and to outshine her sister, both believe themselves to be good people. They arrive in the so-called Good Place and are convinced of it. However, the entire game is designed to have bad people torment each other, creating a false illusion of the Good Place, until Eleanor, who has always thought she mistakenly entered the Good Place, realizes through her ongoing efforts to become a better person that the Good Place she’s been told about is a lie — it’s actually the Bad Place! The game is exposed, and everyone’s memories are wiped to restart. The second round of the game begins. I’m really looking forward to season two. [So excited!]

What’s interesting about this show is the way it redefines "Good People" and "Bad People." You realize that indecision can be just as damaging to others, and that impure motivations definitely don’t count as good deeds. In the game, four people who aren’t really good become a united team, and each of them gradually starts to resemble a good person. Bad can slowly become good, and Eleanor is fortunate enough to encounter a good teacher, Chidi. I wonder what will happen in the rebooted game if Chidi and Eleanor are not designed to be soulmates. I’m really excited to see the next part of the story.

How people should behave in a place where they don't belong

The protagonist, Eleanor, discovers after her death that she has arrived in "The Good Place." Opposite to it is, of course, "The Bad Place." She soon realizes that this is a system error — she was not a kind and friendly person in life. She treated her friends harshly, betrayed trust, was rude, and made a living by deceiving elderly people into buying useless medicine. Compared to other residents of The Good Place — a college professor dedicated to studying ethics, a wealthy young woman who does charity work — The Good Place is certainly not where she belongs. "A mediocre place," she repeatedly complains. She wishes that there could be a middle ground between absolute good and evil, so that someone like her — neither an extremely evil person nor someone who excels — could have a place to fit in.

This is a short comedy with an interesting concept and character setup. But what really interests me is the dilemma Eleanor faces: How should people behave in a place that doesn't belong to them? All my life, I’ve been just an ordinary person in a group. My friends have extraordinary personalities and abilities. Whether in high school or university, I always felt like a stain, the black sheep of the family. (Although the black sheep can be quite cute.) This pressure made me quickly lose confidence. I wallowed in self-pity, filled with jealousy and wariness, without trying to make any changes or efforts. I wanted to overcome this situation. I once thought I had resolved the conflict — that I only needed to boldly admit my mediocrity and give up on unrealistic expectations. However, this series gave me a small revelation: mediocrity and ignorance are also temporary states that can be improved. In fact, I can become a better person, and being in a state of change is a good environment for growth. However, if I admit that "The Good Place" is where I long to be — rather than willingly enduring permanent exile in the desert of self-importance or actively sinking downward — then I must endure more life experiences and setbacks.

Today, I read a sentence: "There are no stupid ideas, only early ideas." Similarly, we can say: "There is no stupid self, only an unenlightened self."